How Healthy Are Our Watersheds?

Ways to Protect Our Watersheds

Stream Buffers

-Riparian Buffer & Rain Garden

-Buffer Handbook

-Sources of native plants

Upper Thornton River Watershed Study

RappFLOW is a member of the Orion Grassroots Network

People, Land and Water at the

Headwaters of the

Rappahannock River Basin

6 Values, concerns, and knowledge of those who own or use the land

From homes on small lots in the villages, to 25 acre residential homesteads in agricultural zones, to commercial shops and service stations along the highways, to farms and forests on hundreds-of-acres parcels, each individual homeowner, landowner, and land user makes the daily decisions that affect landscaping, stormwater management, stream buffer vegetation, animal and crop management, road maintenance, and the myriad other practices that in combination determine the quality and health of their watershed. These practices derive from individual and family history, values, aesthetics, economics, background knowledge, and know-how. Understanding these values, concerns and knowledge is essential to the development of cost-effective strategies for public education and policy.

In this study, we used several methods to identify the range of values, concerns, knowledge and practices among the full range of stakeholders. Four of these methods are discussed here: 1. a mailed questionnaire survey; 2. consultations with individual landowners; 3. observations at public hearings related to watershed protection; and 4. work with subwatershed groups.

6.1 Mailed questionnaire surveys

In January 2006, RappFLOW mailed 998 surveys to all known addresses of residents and landowners in the subwatersheds of the Upper Thornton River Watershed.. Respondents were offered a free aerial photo of their property as an incentive to return the survey.[20] One hundred sixty-two persons responded to this survey. Respondents represent a good spectrum of size of landholding and years lived there. In 2008, the survey was repeated in the Hughes River subwatershed and 88 persons from Rappahannock, Culpeper, and Madison counties responded.

The survey offers 17 answers for what a person values the most in their watershed. Scenery (82), Privacy (77), and Quality of life (77) are the three answers most frequently chosen by respondents. Income from farm (7) or Income from forest (1) were chosen as highest priority values by very few respondents. The survey offers 12 water issues of possible concern. Out of these, quality and/or quantity of drinking water is the most important issue to the most people. The first 157 respondents answered this question in the following way:

Three water issues that concern me the most are the following:

Answer choice |

#

out of 157 |

b. quality of well water |

95 |

a. adequate supply of good drinking water |

83 |

h. bacterial contamination of stream water |

56 |

g. trash in the streams |

40 |

l. need to help clean up the Chesapeake Bay |

35 |

j. nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) in streams and ponds |

31 |

f. stream bank erosion |

30 |

k. loss of fish species in waterways |

26 |

e. sediment in streams and ponds |

19 |

d. floods |

18 |

c. sufficient water for livesk |

13 |

i. algae in ponds |

7 |

Table 3: Water Issues of Most Concern

The survey offers 19 possible threats to the watershed, and asks respondents to choose the THREE that concern them the most. The three threats of most concern to the most people include: Population growth (32%); Subdivision of land parcels (32%); and Public sewage treatment plant discharge to streams (29%). More than a third of respondents said that “bacterial contamination of stream water” is a major issue, but fewer than 10% said that livesk in streams and ponds is a major concern to them, and lack of forested buffers along streams and ponds is a most important threat to only 17 respondents.

The first 157 respondents answered question 8 as follows:

Three threats to my watershed that concern me the most are:

Threat |

#

choosing |

m. subdivision of land parcels |

51 |

l. population growth |

50 |

b. public sewage treatment plant discharge to stream |

45 |

e. pesticides and herbicides |

41 |

a. septic tanks & other private sewage disposal |

31 |

k. commercial development |

27 |

g. loss of farms |

25 |

n. agricultural runoff (nutrients) |

21 |

s. invasive species |

20 |

c. erosion and sedimentation from driveways and private roads |

20 |

i. conversion of forests to other land uses |

19 |

p. lack of forested buffers along streams and ponds |

17 |

f. livesk in streams and ponds |

16 |

d. stormwater runoff |

15 |

h. clear cutting of forests |

15 |

j. traffic |

11 |

q. stream bank erosion |

11 |

o. residential runoff (nutrients) |

6 |

r. wildlife in streams and ponds |

3 |

Table 4: Threats to My Watershed that Concern Me the Most

The responses reveal an opportunity for education regarding relationships among forested riparian buffers and those issues that most concern people, such as clean and plentiful drinking water and bacterial contamination of stream water. The major concern about public sewage treatment plant effluent to stream, in contrast to low concern about lack of riparian buffers and livesk in streams, provides good opportunities for education regarding sewage treatment plant effluent versus impact of land use practices and other nonpoint source pollution issues.

The major concerns about population growth and land subdivision provide good opportunities for public education about conservation tools such as easements.

“I support expenditures of public money on watershed protection and restoration.”

This statement was answered by 144 respondents. Of these, 92 percent in the Upper Thornton survey answered “yes.” In the Hughes subwatershed survey, only 4 out of 88 answered no to this question.

The survey offers 18 possible individual and community efforts on watershed protection.

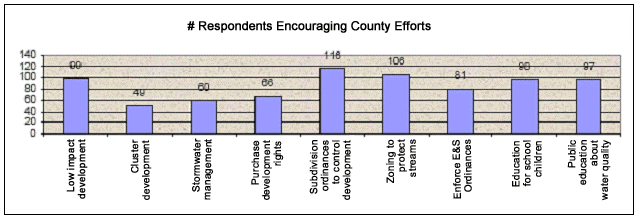

Respondents checked all items they encourage. Nearly all (153) respondents to the survey checked at least one of these items. The following chart shows the number of respondents who encourage certain efforts that are now or might be supported by our county government. Ordinances and zoning were chosen by even more respondents than were education items.

Chart 1: County Efforts Encouraged by Landowners

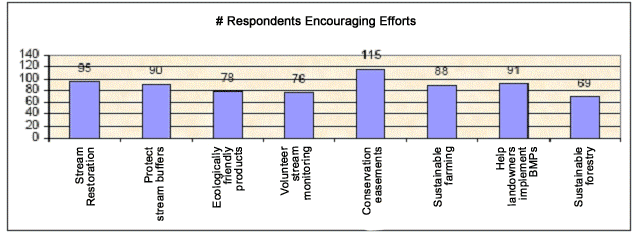

The following chart shows the number of respondents who encourage efforts typically undertaken by landowners with assistance of governmental or volunteer organizations.

Seventy-five percent (115) of respondents encourage conservation easements, which is consistent with the concerns about population growth and subdivision of land parcels in question 8.

Chart 2: Landowner and Volunteer Efforts Encouraged by Respondents

6.2 Consultations with individual landowners

In the spring of 2007, RappFLOW volunteers with technical assistance from the CSWCD conducted assessments of 11 residential and commercial properties in Sperryville along the Thornton River and discussed with the landowners their objectives for the properties.[21] This was part of a pilot test of a program for providing cost-sharing assistance to riparian landowners to improve land management practices on non-agricultural land. The purposes of the assessment were to identify possible improvements in land management, especially stream buffer vegetation, that would reduce nutrient runoff and sedimentation in the river, and to work with the landowners to identify what assistance they might require in order to implement such changes.

For one of the commercial sites, both the site itself and the landowner objectives allowed for a full buffer vegetation restoration project, the Old Schoolhouse buffer restoration. This site was improved through more than 1000 volunteer hours of work, and is serving as a training ground for volunteers as well as public outreach and education site.

- For three of the commercial sites, the site itself does allow for improvement in the buffer vegetation, and one of the landowners has implemented one recommendation -- to mow higher. The other two cases required more technical assistance than can be provided on a volunteer basis. For three of the commercial sites, neither the site itself nor the landowner objectives will allow for any improvement or restoration of vegetative buffers or changes in the land use. The reason is that all of the riparian buffer zone is currently being used for commercial purposes and there is no space to add vegetation.

- One of the four residential sites is ideally buffered and the landowner is fully supportive of maintaining the land in that condition. One of the residential sites would benefit from additional vegetation in the buffer area, but the landowner’s decision to sell the property defeated efforts to invest in improvements to the property. The other two residential sites would benefit from additional vegetation and the landowners do not want to change their land management practices.

RappFLOW volunteers have also conducted individual conversations with dozens of landowners in the context of public education events and workshops. In general, for the individuals who attend such events, it can be said that they are very much interested in “doing the right thing” for their land and the environment, and that their needs for technical assistance, education and advice are wide-ranging.

6.3 Participation in Public Hearings

Hundreds of citizens participated over the past few years in public hearings on issues related to watershed and water quality protection. The opinions expressed in these public forums – by both the public and county officials -- provide insights into the range of values and knowledge among landowners and citizens. Three examples included the following:

- public hearing on the subject of sludge ordinance;

- public hearings on proposed Tier III “significant waters” designation for the Hazel River;

- public discussions concerning proposed permit for discharge of sewage treatment plant effluent to the Rush River.

In the case of the sludge ordinance issue, the courthouse was packed to overflowing with citizens, nearly all of whom wanted the County government either to defend the county’s existing ban on sludge in legal actions against the Commonwealth, or to devise a very tightly controlled alternative ordinance that would effectively ban sludge applications in a legally defensible manner. The public clearly wanted to protect soil and water from contaminants known to be in biosolids/sludge.

In the case of the Hazel Tier III designation, the citizens best prepared to speak on the matter at the hearing were a small number of landowners on the Hazel River who feared the potential of future limitations on their land use due to the possibility of future changing regulations by the US EPA or the VA DEQ. While the majority of landowners on the Hazel River were aware of the issue and supported the designation, they did not appear in person at the hearing. The Board of Supervisors voted to disapprove the designation for Tier III protection on the basis that they did not wish to invite any unnecessary regulation from the federal or state government.

In the case of the Town of Washington’s application to the VA DEQ for permit to discharge sewage treatment plant effluent to the Rush River, a great many citizens became involved both in public hearings and in task force meetings.[22] Probably as a result of the extensive public inquiry and concern, the VA DEQ issued the town a permit containing the most stringent requirements for nutrient removal of any such permit in the DEQ history. The public concern also resulted in the collection of considerable additional baseline data on water quality in the watershed, both by the DEQ and by RappFLOW volunteers.

6.4 Subwatershed Landowner Groups

Several groups of landowners within a particular subwatershed, or whose property is adjacent to a particular major stream, have worked together on various issues of importance to them. Four such groups over the past four years have included the Friends of the Rush, Hazel River Task Force, Friends of the Hughes, and the Jordan River Landowners supporting Scenic River designation for the Jordan River. RappFLOW has provided scientific and technical assistance to these groups, in the form of maps of their watersheds, aerial photos, research on relevant regulations, water quality sampling, and coordination with relevant state agency programs. Through these efforts it becomes apparent that groups of landowners will work together most readily when there is a clear, defined, immediate threat to water quality or to their property rights. Some landowners will work together to take advantage of opportunities that could result in added protections for their streams or neighborhood.

Next: Public Policy: Local Government

Protections for Watersheds

Back to TOC